This article starts with the basic concepts of the Python logging library to understand its execution flow and some details that might be overlooked.

Log Levels

The logging library has 5 preset error levels, plus a NOTSET level, which is the default value for a logger.

CRITICAL = 50

ERROR = 40

WARNING = 30

INFO = 20

DEBUG = 10

NOTSET = 0

The logging library also supports custom error levels. As seen in the source code above, there are 10 numeric positions reserved between different error levels, allowing us to add more detailed error levels on top of the preset ones.

import logging

logging.addLevelName(31, 'SERIOUS WARNING')

logger = logging.getLogger('log')

logger.warn('warn info')

logger.log(logging.getLevelName('SERIOUS_WARNING'), 'serious warn')

For example, by adding an error type SERIOUS WARNING with a value of 31, you can use the log method to output errors of this level.

You can also override the preset error levels in logging, such as changing WARNING to SERIOUS WARNING.

logging.addLevelName(30, 'SERIOUS WARNING')

logger = logging.getLogger('log')

print(logging.getLevelName(30)) # SERIOUS WARNING

LogRecord, Formatter

Each log in the logging library exists in the form of a LogRecord. When a logger is called to print a log, a LogRecord is automatically created, containing a large number of attributes related to the log, including the user-provided message.

| Attribute Name | Format | Description |

|---|---|---|

| asctime | %(asctime)s | Log creation time in a readable format |

| created | %(created)f | Log creation time obtained via time.time() |

| filename | %(filename)s | File name part of pathname |

| funcName | %(funcName)s | Function name where the log was output |

| levelname | %(levelname)s | Log level in string form |

| levelno | %(levelno)s | Log level in numeric form |

| lineno | %(lineno)d | Source code line number where the log was output |

| message | %(message)s | User-provided formatted log content |

| module | %(module)s | Module name part of filename |

| msecs | %(msecs)d | Millisecond part of the log creation time |

| name | %(name)s | Name of the logger |

| pathname | %(pathname)s | Path of the source code |

| process | %(process)d | Process ID |

| processName | %(processName)s | Process name |

| relativeCreated | %(relativeCreated)d | Milliseconds relative to the logging module load time |

| thread | %(thread)d | Thread ID |

| threadName | %(threadName)s | Thread name |

logger = logging.getLogger('log')

logger.warning('a warning message') # a warning message

When executing the above code, you will find that the logger does not output the various attributes of the LogRecord listed, only the message content. This is because the LogRecord is merely an object carrying the content and attributes of each log, created when a log is generated. The log output format is determined at the time of output, controlled by the Formatter. The Formatter is responsible for converting a log (in the form of a LogRecord object) into a readable string. By default, the format is %(message)s, so when no Formatter is specified, only the content provided by the user is output.

Logger, Handler, Filter

The Logger object is the most commonly used object in the logging library. It mainly serves three purposes:

- Exposes methods like info, warning, error, etc., allowing applications to create logs of corresponding levels.

- Decides which logs can be passed to the next process based on Filter and log level settings.

- Passes logs to all related Handlers.

The Logger object can also be inherited, allowing one Logger to pass LogRecords to its parent Logger.

Handlers are responsible for writing logs to their final destination, which could be a file, email, memory, queue, etc. Since a Logger can have multiple Handlers, each Handler can set the level of logs it receives and apply Filters. In other words, logs of different levels can be output to different destinations.

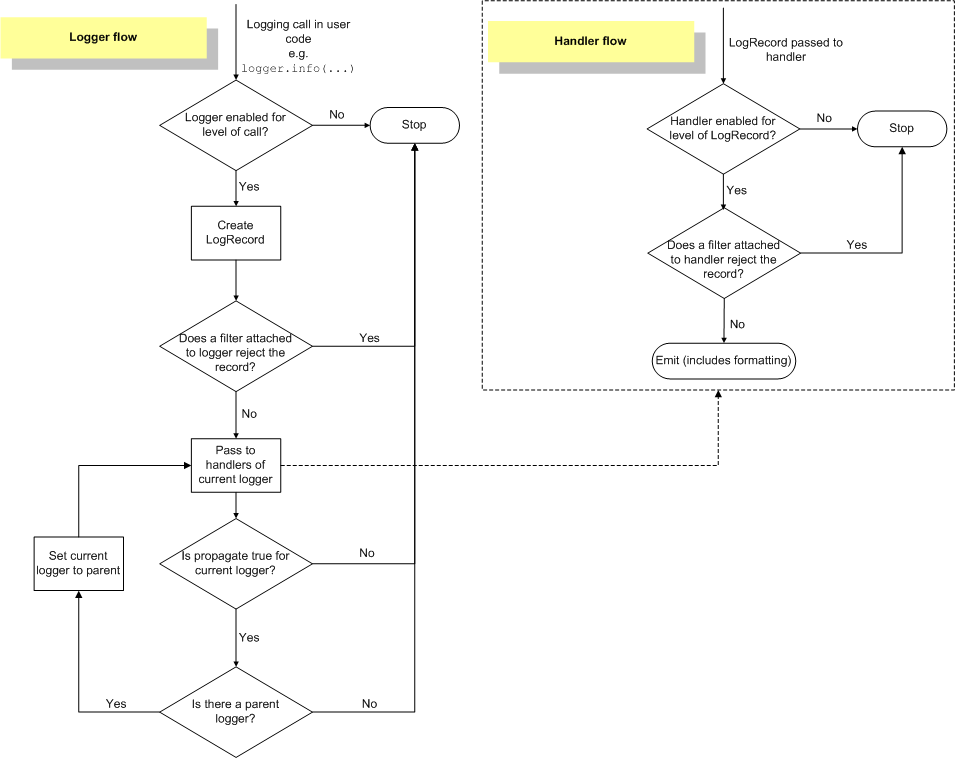

The official Python documentation provides a flowchart of how logging processes logs.

Here, we might have a question: if setting log levels for Logger and Handler already indicates which logs to process and which not to, why do we still need Filters?

Compared to log levels, Filters offer richer customizability and can implement finer-grained control on Logger and Handler. For example, if you want to record only logs longer than 10 characters, you can achieve this with the following code:

class CustomFilter(logging.Filterer):

def filter(self, record):

return len(record.msg) > 10

logger = logging.getLogger('log')

filter = CustomFilter()

logger.addFilter(filter)

logger.warning('a warning message') # a warning message

logger.warning('a warn')

logger.warning('another warning message') # another warning message

Logs shorter than 10 characters, like the second log, will not be output.

Some Practical Experiences

During the use of the Python logging library, we discovered some easily overlooked details that might lead to unexpected situations. Here is a summary.

Logger Inheritance Chain

Logger objects have an inheritance chain. When using the logging.getLogger() method to get a logger, you get the root logger. If you pass a parameter to the getLogger method, you get a child logger.

root_logger = logging.getLogger()

sub_logger = logging.getLogger('log')

print(sub_logger.parent == root_logger) # True

The official logging documentation recommends using __name__ as the parameter for getLogger. __name__ is the module’s path name. For example, using logging.getLogger(__name__) in the utils.log package is equivalent to executing logging.getLogger('base.db'), thus creating a logger named base.db, which inherits from the root logger.

If we also create a logger in base, logger.getLogger('base'), then the base logger also inherits from the root logger, but the inheritance order of the db logger is modified to inherit from the base logger.

root_logger = logging.getLogger()

db_logger = logging.getLogger('base.db')

print(db_logger.name) # base.db

print(db_logger.parent.name) # root

base_logger = logging.getLogger('base') # base

print(db_logger.name) # base.db

print(db_logger.parent.name) # base

In other words, we can obtain any level of logger using the xxx.xxx format, but these intermediate loggers may not necessarily exist.

Logger’s Peculiar Default Behavior

root_logger = logging.getLogger()

root_logger.info('root info')

Executing the above code, you will find no output. However, if you log a warning level log, it can be output.

root_logger = logging.getLogger()

sub_logger = logging.getLogger('sub')

print(root_logger.level) # 30 = WARNING

print(sub_logger.level) # 0 = NOTSET

Printing the default level of the root logger reveals that 30 corresponds to WARNING, meaning only levels higher than WARNING will be output. INFO, corresponding to a value of 20, is lower than WARNING, so by default, the root logger will not accept INFO level errors.

However, only the root logger has a default level of WARNING, while other loggers have a default level of NOTSET = 0.

root_logger = logging.getLogger()

sub_logger = logging.getLogger('sub')

root_logger.info('root info')

sub_logger.info('sub info')

Executing the above code, you will still find no output. Given that other loggers have a default level of NOTSET, why is INFO, which is higher than NOTSET, not output?

When a logger’s level is set to NOTSET, if it has a parent logger, it will pass the log to the parent logger for processing. Only when the logger is a root logger or its propagate attribute is set to False will it handle the log itself. Let’s modify the code above.

sub_logger = logging.getLogger('sub')

sub_logger.propagate = False

sub_logger.info('sub info')

sub_logger.warning('sub warn') # sub warn

In the code above, the propagation feature of the logger is disabled, so the logger will handle errors itself. However, the INFO level log is still not output. If you output the sub_logger.handlers attribute, you will find that by default, the logger has no handlers, explaining why logs cannot be output. However, the next line outputs a WARNING level log, which contradicts this assumption. What is the reason?

Tracing the source code reveals that when a logger needs to handle logs itself and has no handlers, it will try to use the handler stored in the lastResort attribute.

The documentation defines lastResort as follows:

A “handler of last resort” is available through this attribute. This is a StreamHandler writing to sys.stderr with a level of WARNING, and is used to handle logging events in the absence of any logging configuration. The end result is to just print the message to sys.stderr. This replaces the earlier error message saying that “no handlers could be found for logger XYZ”. If you need the earlier behaviour for some reason, lastResort can be set to None.

Therefore, when a logger has no handlers, it can still output logs of WARNING level and above.

References

Python Logging Library Summary - Possibly the Best Summary of the Logging Library So Far - Juejin